Richard Carrier is a prolific writer on ancient history, atheism, and naturalistic philosophy. I started reading him in the 1990s when he wrote articles for the early Secular Web. I especially enjoy his works on the ahistoricity of Jesus. However, his case for the reduction of morality to a kind of instrumentalism, for morality’s being “natural” and “scientific” because it’s a matter merely of learning how to get what we most want, is frustrating because it combines confusion with hubris. Still, various interesting issues crop up in his discussion, so a critique is in order.

By way of providing some background, I should say that there are three paramount theories in moral philosophy: deontology (we ought to do our duty, because the form of action is most important), consequentialism (we ought to act in the way that has the best results), and virtue ethics (we ought to be the best kind of person). Carrier thinks that although philosophers have been debating these theories for centuries, all three views are the same. They reduce to each other and what emerges is instrumentalism, a reduction of moral imperatives to “hypothetical” or conditional ones. So the meaning of “Thou shalt not commit murder” is clarified when we translate it into a conditional imperative that makes reference to the means needed to achieve a desire, such as “If you want to stay out of jail or have self-respect or avoid being killed in return (or insert some other desire here; generally it’s ‘If you want to be happy…’), then you shouldn’t kill an innocent person.” For me, the question whether the three leading moral theories are in conflict is a tempest in a teapot, since I think naturalism has more radical implications for morality, which I’ll come to in the last section below.

But let’s look closer at Carrier’s argument as it’s formulated in his blog’s article on why moral imperatives are a posteriori and natural, meaning why they’re empirical like all other purely factual statements. Carrier’s opponents are two kinds of moral realists who both maintain that moral statements are true or false as opposed to being, say, nonrational expressions of feelings. There’s the theist who trusts that morality is supernatural in that it derives from God, and then there’s the atheist who thinks morality is non-natural in the same way that qualia or normativity in general are, in that their elucidation is beyond the purview of scientific methods, but not beyond philosophical ones. Carrier is aghast because his brand of atheism gives no quarter to theism, and his secular humanism is progressive so he’s opposed to defeatism with respect to the mission to solve all mysteries in the world. Contrary to Nietzsche, the sky isn’t falling just because God, the traditional guarantor of morality, is fictitious; liberal values are secured by reason, not faith. And instead of declaring that some parts of the world are incomprehensible, we should be methodical in our naturalism: we should assume that everything is naturally explainable until proven otherwise. In particular, morality is both real and natural, Carrier says, because it’s about the possibility that some actions are better or worse at achieving our best desires. Those desires are the ones we care about most and the ones we would have were we presented with all the relevant information bearing on ourselves and the world, and were we to think logically about what we most want out of life.

What’s Natural?

Carrier pontificates about how this or that is obviously “natural” in that it’s a part of the scientifically-explainable universe. For example, social properties are just as natural as quarks and sodium, he says, since sociology reduces to physics via psychology, neurology, and chemistry. The greater complexity of social systems is no matter, since sodium is likewise ‘more complex than “just quarks in motion,” which is why sodium is different from uranium, for example, even though both are just “quarks in motion.”’

There are at least two problems with this. First, although he grants that “brains interacting in social systems behave in ways that reflect the structure and behavior of the social system,” he doesn’t grasp that a scientific model has implicit meanings, or connotations, as well as explicit ones (denotations). It doesn’t matter if minds are nothing but brains, if the sets of symbols needed to explain the two orders are incommensurable. A social system may be metaphysically nothing but “atoms in motion,” but there is no sense of “motion” that explains both what atoms and societies do, without palpable equivocation. The word “motion” is defined differently in sociology and in physics. For example, a particle’s velocity is not like a political party’s motion to pass a bill. And reducibility applies to theories, not to the things to which the theories refer irrespective of how they may be understood using different languages or conceptual frameworks like sociology or physics. So denotatively or extensionally, that is with respect to the immediate reference of words, the meanings of “society” and “huge group of atoms” may be identical, but that doesn’t mean there’s a single, coherent set of concepts for explaining what societies and atoms do as seen from different orders of magnitude. Implicitly or intensionally, that is with respect to the words’ indirect meanings in virtue of their relation to background concepts, sociology isn’t reducible to physics, because the full meanings of the terms used to explain what happens in a society as such don’t translate into psychology or neurology or chemistry or physics. Only the extensions or the referents are assumed to be ultimately the same, regardless of our inability to explain without gaps how their identity manifests in the different levels of behaviour. The behaviours perceived from different vantage points, such as those of an appalled American voter witnessing her country’s cultural descent into madness, and of a blurry-eyed scientist staring at a computer screen at CERN, are not at all the same in that they’re not explainable by means of any single coherent set of symbols. You need at least two theoretical discourses to be able to predict what will happen at those levels of being.

Does this mean we should reserve “natural” for our talk about the fundamental, physical level of the universe? Or should we empty “natural” of its content by saying that everything in the universe is natural as long as it’s “scientifically” explainable? The second problem here is that there’s no strict sense of “science” that applies to physics, biology, and the social sciences such as economics or sociology, let alone to both ancient and far future science. At best, there’s a loose sense of “rationality,” according to which these thinkers are “scientific” as long as they think logically about the evidence gathered from their senses. But this loose sense of scientific rationality wouldn’t rule out theological or conspiratorial positing of gods or aliens to explain certain data. After all, no philosophical rationalist who thinks that some statements are rationally justified “a priori,” or without appealing to the senses, thinks the senses have no bearing on logic. Even were we gifted with an innate rational faculty, the rules of reasoning would have evolved or been intelligently designed to help us in the perceivable, outer world; without a world in which to operate, logic would be useless. The paradigmatic instance of a priori reasoning is Descartes’ inference that even if his senses deceive him about the existence of an external world, he can be confident that his thoughts exist, since his doubts would be thoughts. And yet Descartes didn’t haphazardly arrive at that discovery, but conceived of it in a plan to build a cognitive foundation not just for theology but for the sciences which deal with that perceivable outer world.

The question, then, is how much weight to give to logic or to the senses. Theologians observe that there’s an external world and then they take off in reckless flights of fancy in making sense of that world, treating poetic myths as though they were science textbooks. Likewise, conspiracy theorists obsess over scant pieces of evidence, attempting to unify them in grand narratives based on only loose associations between them. You might doubt that those mental exercises are sufficiently empirical to be scientific. But recall that string theory is all the rage in physics, and that string theorists resort to math more than to observation. As Morris Kline explains in Mathematics: The Loss of Certainty, “there is not one body of mathematics but many…What then is mathematics if it is not a unique, rigorous, logical structure? It is a series of great intuitions carefully sifted, refined, and organized by the logic men are willing and able to apply at any time…It is a human construction and any attempt to find an absolute basis for it is probably doomed to failure.” In particular, mathematicians disagree about what constitutes proof and the acceptable principles of logic and axioms, as well as about the sense in which mathematical entities are supposed to exist (310-12). In short, mathematics has a problem with relativism, as do all other forms of reasoning in the postmodern age. So string theorists have their intuitions, which may be little more than gut-level convictions or articles of naturalistic faith, and theologians and conspiracy theorists have their opposing intuitions. Hurray, then! If string theory is scientific, it’s “logic,” “rationality,” and “science” all around!—as long as we’re willing to debase the meaning of those words to unify the worlds they deal with in some megaverse called “nature.” Indeed, physicists entertain the possibility that there are infinite universes regulated by infinite sets of laws. In what interesting sense would all of those universes be “natural”? If physicists can posit non-natural domains, using the most elite forms of reasoning, what’s the “naturalistic” basis for condemning theologians for relying on faith in their positing of heaven and hell?

There’s a better way to understand the difference between the natural and the non-natural. There are two senses of “natural,” the epistemological and the etiological. Epistemically, we can say as I’ve just gone over, that “nature” corresponds to that which is discovered using certain cognitive techniques. It’s then an open question whether, if two disciplines apply different methods of inquiry, they both deal with nature-in-the-epistemological-sense; the answer would depend on just how estranged are those methods from each other. (This kind of nature is often thought to be metaphysical, but the metaphysical notion reduces to the epistemological as soon as scientific methods are brought in to explain why, say, gods and ghosts don’t count as natural.) By contrast, according to the etiological sense of “nature” which Carrier has completely missed, something is natural if it has a certain kind of origin. Specifically, an event is natural if it’s produced entirely by an impersonal series of causes and effects. Naturalness in that sense is opposed to artificiality, that is, to events that originate from intelligent design or free choice, from leaps of faith or reflexive instincts, and in general from the cogitations of living things. Given this second sense of “natural,” morality is unnatural. Indeed, the impetus of Carrier’s case for the instrumental basis of morality presumes there’s only one relevant sense of “natural,” whereas there are two.

Carrier’s Naturalistic Fallacy

Carrier goes on to argue that morality is just a special case of normativity and that normativity is clearly natural since scientists themselves attempt to live up to standards. Says Carrier, “The sciences discover and prove normative propositions all the time: best practices in surgery, engineering, agriculture, and every other field, are all normative propositions about what we ought to do to achieve certain goals. They are empirically discovered and proved as securely as any other facts of the world.” Thus, just because something like morality is normative doesn’t make it unscientific or unnatural. Moreover, says Carrier, “We discover normative propositions, in all the practical sciences (like medicine and engineering) as well as in moral reasoning, by discovering what people desire (in the latter case, what they want out of life, the kind of person they want themselves to be, how they want the social system they must interact with to treat them, and so on) and by discovering what behaviors best obtain those desires (and by extension what habituated virtues will most reliably cause those behaviors).”

Carrier thinks, then, that the difference between a non-moral but normative imperative, such as “A surgeon ought to suture her patient after surgery, if the surgeon wants to save her patient’s life,” and a moral imperative, such as “A person shouldn’t steal if she wants to be happy,” has to do with their content, not with their form. As Carrier says,

Moral judgments operate exactly the same way as surgical judgments. The only difference in fact is that surgical judgments pertain to the goal of surgery, while moral judgments pertain to the goal of morality.

Which means, once you identify the goal of morality, you are half way to discovering true moral facts. Just as once you identify the goal of surgery, you are half way to discovering true surgical facts.

And since moral facts are by definition (by which I mean, the only definition of any use that corresponds to how nearly everyone uses these words in practice) “that which a person ought to do above all else,” you need to identify that which a person really would want above all else (if they were adequately informed of what’s relevantly true)…

That’s morality.

Everything else is false.

In his book, Sense and Goodness without God, in the section “The Goal Theory of Moral Value,” Carrier identifies the ultimate value that suffices for morality: “On close analysis, I believe there is only one core value: in agreement with Aristotle and Richard Taylor, I find this to be a desire for happiness. I believe that all other values are derived from this, in conjunction with other facts of the universe, and that all normative values are what they are because they must be held and acted upon in order for any human being to have the best chance of achieving a genuine, enduring happiness” (2.1.1).

As you can see, he speaks there more broadly of “normative values” as though these were the same as moral ones, which raises the question whether the surgical imperative, for example, is indirectly moral. If happiness is our ultimate goal, all other goals must be subordinate to it, so ultimately the surgeon who performs her job well, according to medical standards, would be acting also to fulfill the moral objective of being happy. If she doesn’t suture her patient, she may lose her job and perhaps then her home and her husband, in which case she’ll be unhappy. So this normative imperative would only directly be about surgery; indirectly, it would be about morality. And yet even that distinction is lost, because there’s no direct way to be happy. Happiness isn’t achievable by any particular act, because it’s an abstract goal that, as Aristotle says, requires us to evaluate the whole life of the person in question. We can lay down the imperative, “If you want to be happy, you ought not to steal,” but avoiding stealing won’t by itself make you happy. Likewise, we could say, “If you’re a surgeon and you want to be happy, you ought to suture your patient after surgery,” and carrying out that instrumental action wouldn’t make the surgeon happy. At best, both would be incremental ways of achieving that ultimate goal, but the same can be said about any other action, no matter how trivial: “If you want to be happy, you ought to turn off the TV when you’ve finished watching it.” “If you want to be happy, you ought to clip your toenails.” “If you want to be happy, you ought to flick away the eyelash that falls on your cheek.” As long as any action achieves some goal that helps you achieve the ultimate goal of being happy, that action would appear to be morally significant, according to Carrier’s analysis. And since there is no immediate way to achieve that ultimate goal, every conditional imperative must have moral force. That’s clearly not so, which means Carrier doesn’t tell us what morality is, after all.

The problem, of course, is that Carrier wants moral statements to be true or false, which he thinks entails that those statements have to be factual. But factual statements are descriptive: they tell us what’s actually, possibly, probably, or necessarily the case. Moral statements are prescriptive: they tell us what ought to be the case. Those aren’t the same, so Carrier’s naturalistic take on morality is bound to fail: he commits the naturalistic fallacy of attempting to derive prescriptions from descriptions without adequate explanation. We can have our perfected science and be omniscient about all the mechanisms that obtain in nature, including all the facts of how human minds and social groups work, and we still could be clueless about what we ought to do in life. Just because you know everything about the actual world, doesn’t mean you know how to change that world for the better. Just because you know everything that’s naturally possible doesn’t mean you know which possibility to select as the ideal one. And just because you know what probably will or what must occur as a matter of natural law, doesn’t mean you know when to resist nature or how to recognize the beauty in tragic resistance.

A hypothetical imperative corresponds to a causal relation. The point is that the stated action directly or indirectly brings about the desired end as a matter of fact. If our desires were morally relevant, science and rationality generally could indeed inform us as to how to achieve those desires and thus how to be moral. But scientists have no business telling us what we ought to desire. They only observe and predict. Some people are psychopaths and can’t be convinced that murdering won’t make them happy. Others are melancholy and have no interest in happiness. Scientists as such could only study such individuals and write up reports about what they do desire. Such scientific studies and explanations wouldn’t make those individuals moral or immoral unless scientists could show that their subjects’ desires are morallyright or wrong. That can’t be done, though. At most, science can show that those individuals are abnormal as a matter of quantitative fact. But popularity isn’t a reliable indicator of morality or even in some cases of truth in general; indeed, it’s fallacious to think otherwise. In fact, most people are indifferent to morality, in that they follow their inclinations without reflecting on whether their behaviour is best. They feel good about themselves not because they’ve done their moral homework, but because they’re afraid to doubt themselves. And as Thomas Kuhn explained, science progresses by overturning normality in the case of conventional wisdom, by following the lead supplied by anomalous observations and subverting the paradigm with a radical new hypothesis. So perhaps the majority will one day tire of their craving for social interaction or for the happiness that’s fleeting at best, and will become Buddhists and live as quasi-sociopaths. Scientists will record the transition in human thinking and a future equivalent of Richard Carrier will have to defer to that majority and declare that the models of morally wise individuals are those who excel at antisocial and melancholic brooding.

Let’s return to the present Carrier’s claim that sciences discover and prove normative statements all the time, just by having best practices. This is slippery. It’s like saying a Neanderthal discovered quantum mechanics just by picking up a rock in which quantum processes occurred. Likewise, scientists may have best practices, but that doesn’t mean their normative status is recognized or justified by employing scientific methods of inquiry. For example, that which makes for the excellence of certain practices in medicine obviously predates the modern science of medicine, since those practices which are considered best are prized because they satisfy the elementary desire to keep living in spite of ailments. Certainly, doctors learned how the body works, correcting their past misconceptions, but the normative status or the rightness of that learning doesn’t derive from logic or from the testing of hypotheses by paying careful attention to data. Those methods of rationality effect the changes in human affairs that are then evaluated as progressive, but the evaluation isn’t established by those methods. People want medical science to advance because our ideal world includes the scenario in which we’re healthy, and science can help achieve that goal, but the ideality of that possible world doesn’t originate from science. No scientist made an observation or an inference which then magically made health a standard worthy of pursuit.

Again, the sciences do have better and worse practices, and so they’re subject to normative evaluation, but the reason why some practices are better or worse doesn’t follow just from the content of any scientific explanation (unless that “scientific” explanation borders on a broader, philosophical argument). Scientists could make advances in their understanding of how to maintain a healthy body, but we might have been a carefree species, throwing health to the wind as soon as our children were raised or assigning the task of raising them to machines. In that case, our “advances” in medical knowledge wouldn’t be widely accepted as such. In this possible world, scientists could make their medical discoveries just the same, but the discoveries would lose their normative status were people at large indifferent to health (short of being suicidal). Alternatively, the positive evaluation of medical practices might have been reversed. Indeed, this re-evaluation has actually happened to some extent, as people in technologically advanced societies think more of quality rather than quantity of life and so frown on the doctor’s insistence of preserving human life under all circumstances.

Inviting the A Priori in through the Back Door

In fact, Carrier slips in a non-scientific and indeed an a priori source of normativity, when he adds the qualifier that morality depends on what we would desire were we adequately informed. Presumably, he adds this to account for immorality as a matter of ignorance. Many people have the wrong desires, which are ones that make them or others unhappy, but if only they were better informed about themselves and how the world works, they would adjust their values and increase the amount of happiness in the world. Unfortunately, this process of informing ourselves is endless. The notion that a pessimistic, antisocial, or melancholy person could be taught to desire happiness and thus to want to act efficiently to achieve that ultimate goal is as naïve as presuming that an Islamist terrorist could be taught to cherish American-style liberty or that a Wall Street banker could be led to convert to full-throated communism or that a diehard Star Wars fan could be supplied with data sufficient for her to switch her allegiance to Star Trek (or vice versa). Again, the fundamental problem is that all such matters of ideality are underdetermined by knowledge of the facts.Star Wars and Star Trek fans can be all-knowing with respect to both of those fictional universes and they might still argue for eternity about which of the fictions is superior. Moreover, no one can say which fact would or wouldn’t be relevant to the question of what we should ultimately value, so Carrier is leaving the door open for knowledge of allfacts in the universe. That knowledge is impossible, so his qualifier is counterfactual, which means it’s a priori. No one will ever stand at the end of the process of gathering knowledge of all the facts that are relevant to the question of what we ought to do in life. If we’re nevertheless to speculate about the result of that process, in a purely academic thought experiment, we must rely on our subjective resources; for example, we must use our imagination. Such a speculation isn’t based decisively on experience and so it’s largely a priori. Carrier’s case for the naturalness of morality is thus self-contradictory.

But without that subjunctive qualifier about what we would value if only we knew everything, Carrier’s instrumentalism would trivialize morality by entailing that all actual, possible, probable, or necessary desires are equally right. All that would matter for morality would be the capacity to satisfy your desire to one degree or another, depending on the extent of your knowledge of how the world works. Thus, a child who can’t open a cookie jar might be called “immoral” for failing to achieve her goal due to her lack of empirical knowledge, whereas any adult whose life runs smoothly, owing to her adequate knowledge of how to get what she wants most of the time, would be “moral.” In short, morality would be the same as efficiency. As long as your actions were rationally and otherwise effectively chosen to achieve your goals, you’d be as righteous as any saint. And there would be no reason to assume that the desire for happiness is the best desire, since there would be no known end of the process of acquiring the relevant knowledge or any need for that process in the first place, without Carrier’s qualifier. So there would be no evaluation of anyone’s goals themselves, and so murderous psychopaths could be as “moral,” that is, as instrumentally efficient as nurses or firemen as long as they all know what they’re doing.

Suppose Carrier says there’s no need for an absolute closure of the rational enterprise of discovering all the relevant facts; the process has gone on long enough, and we’ve already learned that the desire for happiness is best. Remember that this wild judgment would differ from the sensible one that the desire for happiness is normal, that most people would say if asked, that they want to be happy. The latter judgment is empirical and could be proven by rigorous polling and scientific studies. The former judgment is utterly non-empirical. Thus, the declaration that some stage in the process of thinking carefully about the facts enables us to discover our ultimate purpose is arbitrary. The choice of our ideals is underdetermined by empirical evidence, so it doesn’t matter where we are with respect to understanding how the world works; we could still be stumped as to how best to respond to that world.

Far from appreciating this problem, Carrier writes, “Nor can we know a priori what they would want when given more information (about themselves and the world).” On the contrary, that prediction must be a priori, because it’s counterfactual and thus it speaks to a fictional possibility which obviously can’t be understood solely by observing the nonfictional world. We can speak of probabilities based on our limited experience, but our prediction of what someone would want if well informed transcends that experience—just as all so-called a posteriori judgments over-generalize from a strictly empiricist, Humean perspective. The a posteriori procedure of generalizing based just on observations of particular instances has never once been realized in humans. That was the essence of Kant’s reply to Hume. When interpreting data, we always rely on our innate ability to model the world and on our background concepts which lend our thoughts their connotative meanings. True, scientific institutions minimize that subjectivity by objectively testing hypotheses, but they replace subjectivity with what Kuhn called the bias of “normal science,” the institutional inertia that prejudices complacent professionals until a cognitive revolution makes their resistance futile. So the dispute about whether moral judgments are a priori or a posteriori is another tempest in a teapot. If the question is just whether moral judgments are empirical, which is to say adequately fact-based to be useful in a real-world application, there is no dispute since no one thinks morality has nothing to do with the outer reality that we perceive with our senses. Even the theists who say faith is more important than reason would disagree only with some naturalists' view that reality is constrained by the extent of scientific methods of investigation.

The Distraction of Happiness

In any case, it’s dubious specifically for a naturalist to think that happiness is the ultimate goal. The ancient Greek concept of happiness was anthropocentric. Happiness for the likes of Hesiod, Homer and Aristotle was a kind of harmony, beauty, and justice which align us with similar qualities found at the cosmic scale. Thus, happiness was achieved by acting virtuously or moderately, avoiding extremes. Like the Daoist who recommends that we go with the flow of nature’s way, the ancient Greek presumed that the natural order is ideal because order is better than the alternative of chaos, and so we ought to pursue happiness because that’s our function as rational creatures in the greater order of things. (For more on the roles of order and chaos in Hellenic culture, see Luc Ferry’s The Wisdom of the Myths.) That dichotomy between order and chaos is childishly human-centered. The unstated reasoning is that chaos is bad, because it makes human life impossible, but we like ourselves, so the world whose order is a precondition of our existence must be as great as us. Of course, we now know that that distinction is also gratuitous. Chaos abounds in nature, as does quantum weirdness which in no respect harmonizes with our intuitions; thus, the harmony, beauty, and justice we secularists might think we discern in natural events are mere philosophical projections that substitute for the more naïve theistic ones. Nature is almost everywhere a profoundly impersonal place. As such, overextending parochial metaphors by calling natural order harmonious, beautiful, or just is as preposterous as ignoring the anomalousness of human activities and reducing them to nothing but particles in motion. And if nature isn’t ideally harmonious, the ancient Greek underpinning of the West’s obsession with happiness is lost. Why follow nature if nature isn’t ideal by our lights?

There’s also a political reason to doubt that moral rightness consists in trying to be happy. Happiness is the overall contentment with your life’s course, but that contentment could be similar to religion in the Marxian respect; that is, the feeling of happiness might be an opiate that dulls the masses’ critical faculties and distracts us from economic and other material injustices. The science of Western medicine, for example, is currently in league with giant pharmaceutical companies dedicated to making people happy in precisely Carrier’s denuded, instrumental sense. Without ever explicitly second-guessing our actual interests, but while subtly steering them in materialistic directions via relentless ad campaigns, drug companies supply us with efficient means for us to get what we want. Are you depressed? Take this drug and feel better. Urinate too often? Here, buy this pill and be happier. Our contentment occurs, however, within politically acceptable boundaries. As long as we focus narrowly on our self-interest, for the sake of the “free market,” and eschew anticapitalistic or antiplutocratic ideals, we fulfill our function as dupes and drones while the upper class that receives a vastly disproportionate share of this system’s profits, especially in the hyper-individualistic United States, pursues something quite different from the beta person’s contentment. The top one percent of multimillionaires and billionaires isn’t interested in moderation or mere satisfaction for themselves. Typically striving with sociopathic indifference to the plight of those haplessly caught in their schemes for global domination, the cynical power elites who have some direct control over the materialistic culture that perpetuates the no-questions-asked, instrumental interpretation of happiness in the West are busy living as gods who’ve abandoned morality in toto. Like the laws which the wealthy can bypass or have rewritten to their benefit, the very notion of moral restraint is anathema to those brave few who have almost no terrestrial barriers and so can genuinely do whatever they will.

Indeed, the hidden implication of the West’s fixation on individual happiness is that this entire culture is literally satanic in the Crowleyan respect. “‘Do what thou wilt’ shall be the whole of the Law,” reads an infamous passage of the Satanic Bible. But only those who are wealthy or otherwise powerful enough to despoil and murder with impunity can be perfectly instrumental, since a whimsical ambition need merely pop into an oligarch’s head and he or she can move heaven and earth to achieve it. This is how Taylor Swift became famous, for example; her wealthy parents bought her stardom. The rest of us are forced to prioritize, to shortchange some of our desires so that we fail in our Rabelaisian task of honouring our freedom by simply doing whatever we want. Happiness for the hindered majority is conventionally regarded as consisting in contentment with our relatively pitiful lot in life. We’re supposed to understand now that there’s nothing specific that all of us should do, no universal human mission, since values and ideals are subjective. There’s nothing more to having a moral purpose than having a desire, and since our desires differ due to many factors, there’s not one moral imperative for all but a plethora of such imperatives. We’re bound to come into conflict, then, just as the rest of the world naturally throws up obstacles before us which few can fully overcome. Again, for most of us, to say that the search for happiness is life’s meaning is to say that we must reconcile ourselves to that disappointing state of affairs and learn to appreciate our small triumphs. As for the glorious minority who are undeterred by any impediment, their purpose is the satanic one of the pure instrumentalist who thinks the evaluation of ultimate goals is irrational or pointless, and so all that matters is being efficient in tailoring means to ends. That esoteric purpose is to fully express every little thought of theirs that strikes their fancy, to celebrate their freedom by doing precisely whatever they want. Power corrupts, after all.

The ambiguity of “happiness” surfaces in Carrier’s definition of the word in Sense and Goodness: “By happiness, I do not mean mere momentary pleasure or joy, but an abiding contentment, a persistent, underlying sense of reverie that makes life itself worth living...” Carrier then quotes David Myers as saying, ‘real happiness means “fulfillment, well-being, and enduring personal joy”’ (2.1.2). But what does contentment have to do with reverie? If you’re content with your life, you’re not likely to attempt to escape from it to a daydream. Likewise, if you’re merely content, well, and satisfied, you’re not yet in a position to feel joy. Joy is great delight or keen pleasure which surpasses contentment. The explanation for these confusions is that, politically speaking, there are two standards of happiness, one of contentment for the moderate, hamstrung masses who can’t afford to be happy in the higher sense that allows for reverie and joy in the satanic, boundless expression of freedom. The members of the hedonistic and enterprising upper class must be encouraged to daydream, not only because they have the luxury of much free time, but because their wealth equips them for the Herculean task of moving mountains to make their dreams realities.

You might be thinking that Carrier has an obvious rejoinder: there’s no Satanism or raw instrumentalism at issue, because a liberal secular humanist who thinks morality is a matter of learning how to be happy can appeal to Mill’s dictum that we should each pursue our self-interest as long as we don’t interfere with each other’s right to pursue theirs. This variant of the Golden Rule assumes we all have an equal right to attempt to reap the benefits of a good life. There would, then, be two problems with Carrier’s use of this principle. First, Mill’s point is consistent with the Kantian one that we’re special because of our autonomy and our creativity, which imply that we impose an artificial world order onto nature. Moral deeds would be etiologically unnatural, indeed precisely anti-natural, contrary to Carrier’s heavy-handed naturalism.

Carrier would need a reason why we should respect each other’s attempts to be happy, even though we’re all really just atoms in motion like everything else. Scientists objectify whatever they study, whereas the Golden Rule assumes that the source of morality is an inviolable subjectivity in each of us, a godlike power to reshape the prehuman landscape to suit our often outlandish ideals. One reason Carrier might turn to is that when we harm others, we impede our efforts to be happy, because our conscience will provide painful reminders that we’ve done wrong, for example. Clearly, the conscience does function in this way for most people. However, we also have a penchant for rationalizing our misdeeds, to reframe the facts so as to minimize our cognitive dissonance. So even those who aren’t psychopaths, who have the capacities for empathy and remorse, often presuppose that their happiness matters more than most other people’s. If such commonplace selfishness is immoral, Carrier’s instrumentalism doesn’t explain why that’s so. On his account, morality is the attempt to be happy, by learning which actions best fulfill your mediate and ultimate desires. Ifit turns out that the possibility of harming someone will provide you only with short-term gain but long-term unhappiness, because your conscience will bother you, you might well calculate that the action isn’t worthwhile from the perspective purely of self-interest. But if you can reinterpret the possibilities to get around your conscience, bringing to bear your powers of rationalization and confabulation, you’ll have no such reason to resist that temptation to harm someone else to benefit yourself.

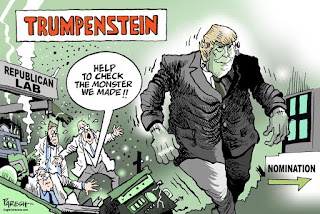

Second, it’s easy to see, on the contrary, that we’re not nearly as equal as Mill’s liberal dictum assumes. The most glaring instance is the class divide between the very wealthy and the masses of poor in the United States and most other countries. Take Donald Trump and a homeless man, for example. Both are biologically and physically similar, but socially they’re vastly different. Trump has billions of dollars, the homeless man has pennies. That wealth inequality is part of what Richard Dawkins might call their extended phenotypes, that is, their external, non-biological bodies. Trump’s wealth allows him to luxuriate in many enormous homes, to fly to any part of the world at a moment’s notice on his private jet, or to take over one of the two official political parties in the world’s most powerful nation. The homeless man is lucky if he can guilt-trip enough people in a day to fund his effort to eke out a coffee and a McDonald’s hamburger. In many ways that count, the two individuals aren’t remotely equal. If squashing that homeless man—or by extension the majority of Americans—is somehow in Trump’s personal best interest, why should he refrain from doing so, given just the instrumental take on morality plus Mill’s Golden Rule? The latter rule is nullified by the overwhelming inequality, so that all that matters to morality, for Carrier, is the instrumental relations between means and the end of personal happiness. If dominating underlings is in an autocrat’s best interest, if that’s what he thinks of as the greatest success and the autocrat flourishes on that basis, Carrier must congratulate him for being a moral paragon. In that case morality has been redefined as satanic (egoistic) ruthlessness, to excuse the extent to which American-style pseudocapitalism has warped the Western psyche.

Again, as a matter of fact, the wealthy do see themselves not just as different from the poor but as superior, and the poor agree because they’d desperately like to be rich. With respect to our capacity to take action to achieve our aims, our extended phenotypes—our material possessions, financial and other resources, social networks and pedigrees—are just as relevant as our biological bodies (and specifically our brains). True, wealth is no guarantor of happiness and our expectations adjust to our circumstances so that a poor person might conceivably feel more content than a rich one. But most people would rather be a sad rich guy than a happy bum. Mill’s dictum, therefore, has no universal application once we shake off the modern humanist’s myths and attend to the real social differences between us. At best, Mill’s principle might be relativized so that it applies only to those who are actually equal to you in the relevant ways. A billionaire’s narcissism might not be able to overcome the logic that one billionaire’s happiness can’t matter more than that of other billionaires, but the wealthy would be free to prioritize their interests over those of the much less powerful masses, without any fear of violating some reasonable liberal principle of morality.

Morality is having the Good Taste to Defy Nature

So much for Carrier’s argument. I’ve said, though, that morality is etiologically unnatural. What, then, is the root of morality’s anomalousness which leads Carrier’s secular opponents to compare it to qualia? Everything we do is similarly unnatural, which means just that nature-as-wilderness can be usefully distinguished from any artificial world. This doesn’t mean we have to be Cartesian dualists, but we should appreciate the logical gaps between explanations of impersonal nature and those of what happens in personal, social, and even some animal domains. Kant was right when he said that morality is opposed to “inclinations” and thus to the natural world. We’re at our most moral when we think our action is right regardless of whether we want to act that way or whether we approve of the action's likely results. Morality depends on freedom from the biological cycles that would confine us to reacting to stimuli or to expressing our genetic, bodily potential. But I don’t follow Kant’s interpretation of morality as being just about rationally self-directing our behaviour, and thus about following the laws that distinguish what I’ve been calling the artificial world we create, from nature.

The deeper reason for morality as well as for artificiality in general is that living things are appalled by nature’s monstrousness. In so far as we react with indignation to the chaos and indifference and unfairness in nature, to the sheer horror of the struggles fought throughout the animal kingdom and of the galactic rearrangements that both create and remove the conditions for life to emerge and to thrive, we may still be acting from the instinct to endure. In that respect, nature would be at war with itself: natural forces would come together to create living things that set themselves apart from the wilderness, counter-creating an artificial territory that displaces their pristine, mindless habitat. As Keith Stanovich says in The Robot’s Rebellion, the genes put us on a “long leash,” allowing us the freedom even to bite the hand that feeds us. This kind of antinatural creativity that occurs especially when animals modify their environment to their advantage is likely an evolutionary stage in a war of attrition that makes for highly specialized adaptations. Proto-giraffes evolved long necks which allowed their descendants to beat their competitors and thrive by reaching higher and higher leaves. And proto-humans evolved the ability to rationally control their minds, which allowed us to thrive by extinguishing or enslaving our competitors and by redesigning the entire playing field, bulldozing forests and mountains, building bridges and dams and concrete cities, and even tinkering with our genetic makeup. Often, then, our antinatural activities are part of an evolutionary long con: we think we’re free and independent, but really we’re just spreading our genes in a new way that will eventually be replaced by some posthuman way of life.

However, we begin to act out of moral obligation rather than just instinct or inclination when we appreciate the aesthetic need rather than just the empirical reason for an artificial world to replace the wilderness. Reason is an exaptation and science is its ultimate byproduct. We exercise instrumental reason when we understand our actions as the means to satisfy our desires, including our desire to flourish. That latter desire may be an instinct that makes us stooges in a drama run by a headless director. But when we stand back and perceive the hideousness of a natural order founded not on a heroic, Olympian struggle against chaos, as the ancient Greeks felt, but on quantum weirdness; when we detach ourselves from practical reason and scrutinize the facts as we experience them from the aesthetic stance, ignoring their utility and evaluating whether nature as a whole is a comforting or an eerily inhospitable place; in short, when we ponder our existential situation and suffer the angst and alienation that generate our aesthetic condemnation of the world, we act against the cosmos out of a tragic recognition that even though we’re often pawns, our defiance is noble.

We’re pawns that know we’re such and so we needn’t indulge in Enlightenment metanarratives like Kant’s or Carrier’s. We’re pawns that can rewrite the rules and build another game board; moreover, we can do this not just because our terrestrial game board still rests atop the larger, natural one, as it were, but because our effort has aesthetic value even though its results will ultimately be negated by the encroaching wilderness. When we take a stand against nature’s inhumanity, as opposed to pretending that our values are so great they’re somehow universal, we rise on behalf of all living things. Yes, that’s rich coming from the most lethal species that’s emerged on earth. But our barbarous slaughter of other species is typically due to our natural inclinations. We destroy the ecosystem not because we’re acting with aesthetic detachment and existential appreciation for life’s tragedy, but because we selfishly want to thrive even at the expense of all other creatures. Thus, human savagery is attributable to nature’s mindlessness: our genes implant us with the aptitude for narrow-minded, Machiavellian reasoning as well as with the urge to survive at all costs. We thereby indirectly destroy ourselves in so far as we’re puppets in nature’s war against itself. By contrast, as aesthetic critics and existential artists, we would seek to preserve the stage that sustains the moral resistance against nature’s ghastliness. Moreover, we’d sympathize with the plight of all creatures plunged into the Potemkin paradise that swirls in the greater void.

This aesthetic creativity is all that’s left of morality after the postmodern erosion of ancient and modern myths. Instead of deferring to blinkered or corrupted priests, cult leaders, or condescending secular authorities, we should each appreciate what’s at stake in life at the existential level. Moral persons are called by their muse to know exactly where and what they are, and to do something honourable with that knowledge. We shouldn’t surrender our autonomy, whether to religious delusions about autocrats in the heavens or to substitute ideologies espoused by politically correct New Atheists like Richard Carrier whose harangues about happiness help maintain outrageous economic inequalities that are our versions of primitive dominance hierarchies. We shouldn’t be content with a technocrat’s narrow conception of normative evaluation, according to which the worthiness of most values depends on their efficiency in achieving some ultimate end, and the worth of that end isn’t explained but fallaciously reduced to its normality. And we should make the best of the horror that ought to follow from philosophical naturalism. We’re moral rather than just socially normal or legally protected or immune to reprisal thanks to our oligarchic dominance, when we act out of distaste for the grotesqueries that could arise only in an abominable universe that mindlessly creates and destroys itself.

Needless to say, this account of the basis of postmodern, naturalistic morality inverts Carrier’s. For him, we’re moral when we’re happy, which is when we’re able to do what we most want. True, most of us want to be happy. But contentment in the teeth of our existential predicament is an appalling breach of our existential responsibility. When we’re content with our meager achievements as these are credited in some myopic and self-destructive neoliberal scheme, ignoring the nightmares and the holocausts all around us, we’re not fulfilling our moral obligation. On the contrary, we’re showing ourselves to be self-centered and uninspired. Great art is usually drawn from great suffering. This is demonstrated by the fact that moving, original art is produced usually when the artist is still languishing in obscurity before achieving fame later in life or after death; the more success she has in her artistic endeavours, the more self-indulgent they become. We must pass through the inferno of existential pain before we can take a worthy leap of faith in carrying out some dignified, albeit doomed artistic project such as the creation of a worthy human life. Rather than being egoistically fixated on the urge to satisfy our puny desires that are often sustained by delusions, we should realize that such contentment is shameful and we should long to feel possessed by a daemonic muse that guides our use of natural resources for the sake of artistic greatness. We shouldn’t do what we most want; instead, we should go to war against our monstrous foe. There’s no sane joy in war. War is a sorrowful labour of last resort. We’d prefer to be happy in an ideal world in which we could feel content, without our self-centeredness being a total disgrace. But we don’t live in a real paradise. We live in an indifferent world in which the intelligence behind our design is an illusion. Mother Nature has already declared war on all living things from the moment they emerged. She’s set us at war with each other and with her zombified appendages that periodically slam into us in the form of natural disasters. To think that our ultimate purpose is for our worldly successes to be rewarded with our feelings of complacency is to lose all existential perspective and to surrender to the enemy.

And this sketch explains, too, why far from being widespread, as in Carrier’s reductive argument, true morality is rare. Whereas Carrier’s account implies that all our actions are indirectly moral in so far as they help make us happy, most people, as I said above, are indifferent to morality. They’re content with the law’s regulating of society, and they assume morality is just an academic subject for dusty old philosophers. Most people would never call a convicted murderer merely “immoral,” since they would assume that that’s an understatement. True, the theistic masses believe their society’s laws derive from divine commandments and that they’re soldiers in a spiritual war between forces of Good and Evil. But they don’t think of spiritual righteousness and demonic rebellion as having much to do with morality. They presuppose that we should follow the Ten Commandments, not because we ought to do what God says, but because God is all-powerful and will reward or punish us depending on whether or not we obey him. This is just the theistic version of the self-centered dupe’s instrumental reasoning that takes for granted our instinct to care mostly about our paltry welfare. So-called divine commandments are always implicitly conditional imperatives that promise eternal happiness or suffering. So religious “morality” is about siding with the so-called greatest power and about rationalizing the inequities that spring from the institutions that depend on such mass gullibility.

In our daily life, most of us are much more concerned with obeying or with bending the law than with whether we’re fulfilling our highest calling. This is partly because proper morality is a philosophical subject, and thanks to its institutionalization, Western philosophy is unpopular. But it’s also because morality is hard. It takes uncanny willpower to stomach the travesties and catastrophes that motivate us to act out of righteous indignation. We don’t often care about morality, because we prefer to be playthings of natural processes than to ascetically detach ourselves even from our animal cravings. We prefer to keep our head down, follow the majority and be normal so that we need exert effort only in calculating the most rational means to satisfy our natural desire to feel good about ourselves on the whole. We don’t want to face the startling fact that all living things are etiologically unnatural in so far as their minds alter their environments and themselves. We don’t want to confront the truth that the abyss between our speck of a planet on which life teems and the astronomically vast universe in which life is vanishingly rare draws us into a tragic conflict with our mindless maker. We’d rather our best actions were fuelled by something other than horror and a feel for the absurd and the tragic. That’s because we are primarily animals, lesser artists, and dupes on long leashes. The desire for happiness is merely normal, as is our cowardice in the face of our only remaining moral obligation. Morality, that is, the grim, knowing commitment to war on nature’s hideousness, is as rare among living things as the latter are in the universe that contributes to the aesthetic worth of our acts of defiance by making them dreadfully for naught.